Parents' and children's perception on social media advertising

Abstract

This article presents the results of research that seeks to analyze the ability of minors to identify the advertising messages received through the most used social networks by this audience (YouTube and Instagram). Children’s aptitude to recognize persuasive intent was measured in a selection of examples taken for this study, as well as the perception that parents or guardians had about the minor's ability to recognize advertising on the platforms analyzed. Results were obtained from a survey applied to dyads in 501 homes in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago de Chile, to children aged 10 to 14 and to one of their parents or guardians. Main results include the notion that more than 50% of children were not able to detect advertising in examples containing ads. Lower recognition percentages were obtained in cases that combined persuasive content and entertainment and were not classified as advertising. For their part, adults perceived that their children recognize persuasive intent to a lesser extent than indicated by the children themselves. An explicit and clear signaling of advertising messages, as well as advertising literacy according to the age of minors could help them discern the content they consume on social networks.

Keywords

Advertising, minors, social networks, Instagram, Youtube, advertising literacy

Palabras clave

Publicidad, menores, redes sociales, Instagram, YouTube, alfabetización publicitaria

Resumen

Este artículo presenta los resultados de una investigación que analiza la capacidad del menor para identificar los mensajes publicitarios que recibe a través de las redes sociales de más uso entre este perfil de audiencia (YouTube e Instagram). Se midió la aptitud de niños y niñas para reconocer la intencionalidad persuasiva en una selección de ejemplos tomados para este estudio. Adicionalmente se analizó también la percepción que sus padres o adultos responsables declararon tener sobre dicha capacidad de los menores. Los resultados provienen de una encuesta aplicada en díadas en 501 hogares del Área Metropolitana de Santiago de Chile tanto a niños y niñas entre 10 y 14 años como a uno de sus padres o adulto responsable. Entre los principales resultados destaca que en los ejemplos propuestos la mayoría de los encuestados (más de un 50%) no fue capaz de detectar publicidad en contenidos que sí la integraban. Los porcentajes de reconocimiento fueron incluso inferiores en aquellos casos que entremezclaban contenido persuasivo y entretenimiento y que no estaban catalogados como publicitarios. Por su parte, padres y madres percibieron que sus hijos reconocen la intencionalidad persuasiva en menor medida que lo indicado por ellos. Una señalización explícita y clara de los mensajes publicitarios, así como una alfabetización publicitaria acorde a la edad de los menores podrían ayudarles a discernir los contenidos que consumen en redes sociales.

Keywords

Advertising, minors, social networks, Instagram, Youtube, advertising literacy

Palabras clave

Publicidad, menores, redes sociales, Instagram, YouTube, alfabetización publicitaria

Introduction

Advertising literacy in the face of new digital advertising formats

Social networks take up a large percentage of online time among young Chileans, especially YouTube and Instagram (VTR, 2019; Feijoo & García, 2019; Cabello et al., 2020) and therefore have become very attractive for commercial brands. Social platforms enable the establishment of a dialogue with target audiences, as well as increased sales and brand familiarity. They have also become an important source of reference that users trust when searching for product or brand information (IAB Spain, 2020).

The fact that the audience is reached via a personal digital device strengthens the invasive nature of advertising messages (Martí-Pellón & Saunders, 2015; Truong & Simmons, 2010). Digital advertising can be perceived as less annoying when it contains humor (Goodrich et al., 2015) or can be skipped or closed (Feijoo & García, 2019). Commercial content that includes rewards, special effects, immersion elements or appearances by well-known people or influencers trigger better attitudes (De-Cicco et al., 2020). Currently, despite their lack of transparency (Van-Reijmersdal & Rozendaal, 2020), there is an increasing presence of messages in which commercial, informative and playful content are mixed, and in which the boundaries between types of content constantly cross (Tur-Viñes et al., 2019; Feijoo & Pavez, 2019).

Recent studies on influencer marketing among young audiences (De-Jans & Hudders, 2020) show that the minors’ ability to interpret advertising messages decreases when influencers do not mention the brand interference on their sponsored content. Furthermore, young people accept the presence of brands and sponsorships in the content presented by their opinion leaders as long as the balance between entertainment and commercial content is perceived as undisturbed in the videos (Van-Dam & Van- Reijmersdal, 2019; Feijoo et al., 2020). In addition to the greater difficulty in recognizing the persuasive intentionality of influencer-supported formats (Rozeendaal et al., 2013), added risks derive from a lack of warnings, given the absence of specific regulation and the credibility these formats are granted (Tur-Viñes et al., 2018; Feijoo & Pavez, 2019). Following the implementation of the COPPA (Children's Online Privacy Protection Act), for example, YouTube has placed more restrictions on this type of content when it is aimed at children under 13 years of age.

In 2018, the Board of Advertising Self-Regulation and Ethics (Consejo de Autorregulación y Ética Publicitaria) (CONAR, 2018) updated the Chilean Code of Advertising Ethics by incorporating a new article (#33) devoted specifically to advertising regulation in digital and interactive media, and social networks. The article specifies that all commercial communication broadcast by these media must be clearly identifiable as such, based on the principles of identification and transparency. With regard to influencers, who mainly disseminate their content on social networks, the article specifies that any commercial link must be clearly and visibly identified so that the consumer is aware that opinions delivered in videos respond to an interest, whether that be economic or in kind.

Therefore, it is necessary to question the level of preparation of minors in the face of new digital advertising formats, that is, their level of advertising literacy. Following Rozendaal et al. (2013), advertising literacy, also called persuasive knowledge, consists of two dimensions: first, the conceptual dimension that implies the recognition of advertising, which is to say the understanding of the commercial source and its intention and of the persuasive techniques of advertising, as well as the bias these introduce with respect to reality; and second, the attitudinal dimension, which is associated with critical attitudes towards advertising. Meanwhile, Hudders et al. (2017) study advertising literacy at the dispositional (possession of knowledge and skills) and situational level (actual processing of a specific advertisement).

A number of research projects on new digital advertising formats (An et al., 2014; Van-Reijmersdal et al., 2017; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017) have shown that conceptual knowledge of the persuasive intentionality of advertising is necessary, but not sufficient for minors to properly process a message (Livingstone & Helsper, 2006; Rozendaal et al., 2011). According to the PCMC (Processing of Commercialized Media Content) model proposed by Buijzen et al. (2010), children apply low-effort cognitive processing when faced with these new digital advertising formats, and do not activate the associative network of knowledge that they have developed about the advertising phenomenon (Mallinckrodt & Mizerski, 2007; An et al., 2014; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017; Van-Reijmersdal et al., 2017). Many of these studies, which focused on videogame advertising, found that the recognition of the advertising intention of a message does not automatically lead to the ability to question and interpret the content received.

Low cognitive elaboration conditions while processing these new advertising formats may be worsened by other reasons such as the fact that the child's attention is concentrated on the recreational aspects of the format, which places the processing of the persuasive message to the background. This is observed in advergaming, (Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017), where the positive feeling induced by the game is likely to be transferred to the attitude about the brand and vice versa (Mallinckrodt & Mizerski, 2007). Consequently, the studies cited here highlight the need to reinforce advertising literacy from an attitudinal dimension, which would be much more effective in leading minors to question and interpret an advertisement. Thus, attitudes such as skepticism (assessing the biased approach of advertising) or liking/disliking are central in this low-effort processing of new digital advertising formats.

In their conclusions, An et al. (2014) emphasize the importance of having minors perceive these new formats as advertising to achieve effective message processing. Hence, this article focuses on the recognition process of the advertising phenomenon. Similarly, the degree of familiarity and experience that the minor has developed with the medium in which the advertising is inserted could also influence the persuasive effect. In addition, the ability to critically confront advertising depends on the development of cognitive skills which gradually appear as children grow older, and therefore the literacy process needs to be appropriate for the age (Hudders et al., 2017).

The role of families in the advertising literacy of minors

Families are key agents in the training of children as consumers (Buijzen, 2014; Oates et al., 2014). Studies carried out in various countries reflect the concern of parents about the advertising their children face (Buijzen, 2014; Oates et al., 2014). On the one hand, parents are aware that children do not have sufficient cognitive skills to understand the nature of advertising and its intentionality. On the other, parents show their concern about the possible negative effects of these messages, such as instilling materialistic values, excessive desire to buy or unhealthy eating habits (Buijzen, 2014).

Regarding the nature of advertising, parents maintain that ads take advantage of the naivety of children who can literally believe what is being advertised to them (Ip et al., 2007; Tziortzi, 2009). Research by Young et al. (2003) among parents from Sweden, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, highlighted that adults recognize that advertising pushes children to pressure their elders to buy the advertised products, that children are excessively vulnerable and that the more advertising minors are exposed to, the bigger the desire they have for the advertised products.

When parents are asked about the means through which their children receive advertising messages, they mainly point to television (Oates et al., 2014) and seem to be less aware of other sources, as concluded by Watts (2004), whose studies confirmed that less than a third of the parents were aware of the marketing activities carried out within schools (school contests, visits, promotions, and others). The academic discussion around linking children to other marketing activities such as the one here studied is relatively much smaller compared to television (Oates et al., 2014).

The presence of parents in a partner-spectator role provides them with an opportunity to mediate the content that minors receive on a multiscreen environment, and to teach them to differentiate between what is real or fiction, and thus promote healthy consumer values (Saraf et al., 2013).

Material and methods

Research objectives and questions

This study specifically seeks to analyze the ability of children to recognize persuasive content on social networks (YouTube and Instagram) by exposing them to selected cases for this study. Minors were asked to identify the messages which are described in Table 2. Their responses were compared with the perception of the adults on the children’s ability to detect such advertising content. Ultimately, this study aims to deepen the level of advertising literacy of minors in the face of new digital formats, especially those that combine advertising and entertainment. The results presented in this article are part of the research project (Fondecyt Initiation N. 11170336) on children, mobile devices and advertising formulated for the purpose of knowing what use is made of and what is consumed by minors aged 10 to 14 years of age living in the metropolitan area of Santiago de Chile, through their mobile devices. This was done to subsequently strengthen their ability to mediate with the advertising they receive through their favorite platforms. This study was designed in dyads to address the phenomenon both from the point of view of the children themselves and that of their parents.

To do this, face-to-face surveys were administered in 501 households, to both boys and girls ages 10 to 14 and to one of their parents or legal guardians. This was performed following a probabilistic design by areas and contemplating an error of ± 4.4% under the assumptions of simple random sampling and 95% confidence. The fieldwork took place between the months of May and July 2018 and, during the visit to each home, adults and minors were surveyed separately. The survey format was the same for both respondents, with the version for adults designed to learn about their perception of the minor's ability to identify the advertising they receive through mobile devices.

To respond to the research goals, the following research questions were formulated:

-

RQ1. Do the surveyed children recognize advertising content in the cases presented?

-

RQ2. Can minors identify standard advertising formats and those that combine persuasive content and entertainment in the same proportion?

-

RQ3. Are there significant differences in the level of recognition of advertising in the selected cases based on the age, gender and socioeconomic status of the minors?

-

RQ4. What percentage of the sample of children correctly detected the presence or absence of advertising in the selected cases?

-

RQ5. What perception do adults have of the minor's ability to recognize advertising in the selected cases?

-

RQ6. What level of knowledge does the child’s legal guardian have of the minor's ability to recognize advertising content in the examples in this study?

Sample description

In total, 1,002 valid responses were obtained from the survey, including both minors and legal guardians.

The age distribution for the minors in the sample was: 60% in the 10-12 age group, and 40% in the 13-14 age group; by gender, 46% were male and 54% female. Regarding adults, most of the responses were obtained from mothers (82%) mostly within the 30 to 45 age range (68.5%).

With regard to the description of the household, in terms of number of members, the most common household had four members (32.7%), followed by five members (24.2%). Regarding education, the head of the household of 75% of the households was a high school graduate and in terms of socioeconomic level, households were distributed as follows: C1 (7.2%); C2 (18.4%); C3 (28.5%) and D (42.9%). Three percent of respondents chose not to provide this data.

Regardless of the socioeconomic level, the members of the sample had a high use of mobile devices, mainly smartphones (99%); to a lesser extent, laptops (52%) and tablets (49%). The main uses are entertainment (83%), communication (77%) and social networking (43%). Consequently, the most downloaded applications were video players (66%), social networks (56%) and games (54%).

Measurements

Given the scant attention paid to advertising consumption in digital environments by minors (De-Jans et al., 2017), this study has an exploratory approach that seeks to shed light on the extent to which minors can recognize the advertising they are exposed to on social networks.

To measure advertising literacy, the survey model designed by Rozendaal et al. (2016), namely ALS-C (Advertising Literacy Scale for Children), was taken as a starting point. This model has been tested on children aged 8 to 12 and involves the analysis of both conceptual and attitudinal literacy. The commercial message recognition variable was selected from this survey to measure advertising literacy from a situational point of view, that is, by having a minor process a specific and real case (Hudders et al., 2017). Considering that the ALS-C model was designed to measure television advertising literacy, it was adapted to the digital context (Rozendaal et al., 2016; Zarouali et al., 2019) and advertising recognition questions with multiple choice answers were defined in the questionnaire. This allowed researchers to integrate the diversity and particularities of the advertising formats present in social networks. Thus, minors were asked the following questions:

- In which of the following YouTube examples do you detect advertising? Example 1; Example 2; Example 3; Example 4; Example 5; I do not see advertising in any example.

- In which of the following Instagram examples do you detect advertising? Example 1; Example 2; Example 3; Example 4; Example 5; I do not see advertising in any example.

The questions were reformulated in the adult questionnaire as follows: In which of the following YouTube / Instagram examples do you think the minor would detect advertising?

Table 2 summarizes the examples used in the questionnaire. There are cases that do not contain advertising, cases that use standard advertising formats and others in which the brand and / or the product appears interspersed with the content.

Results

Level of advertising recognition of minors

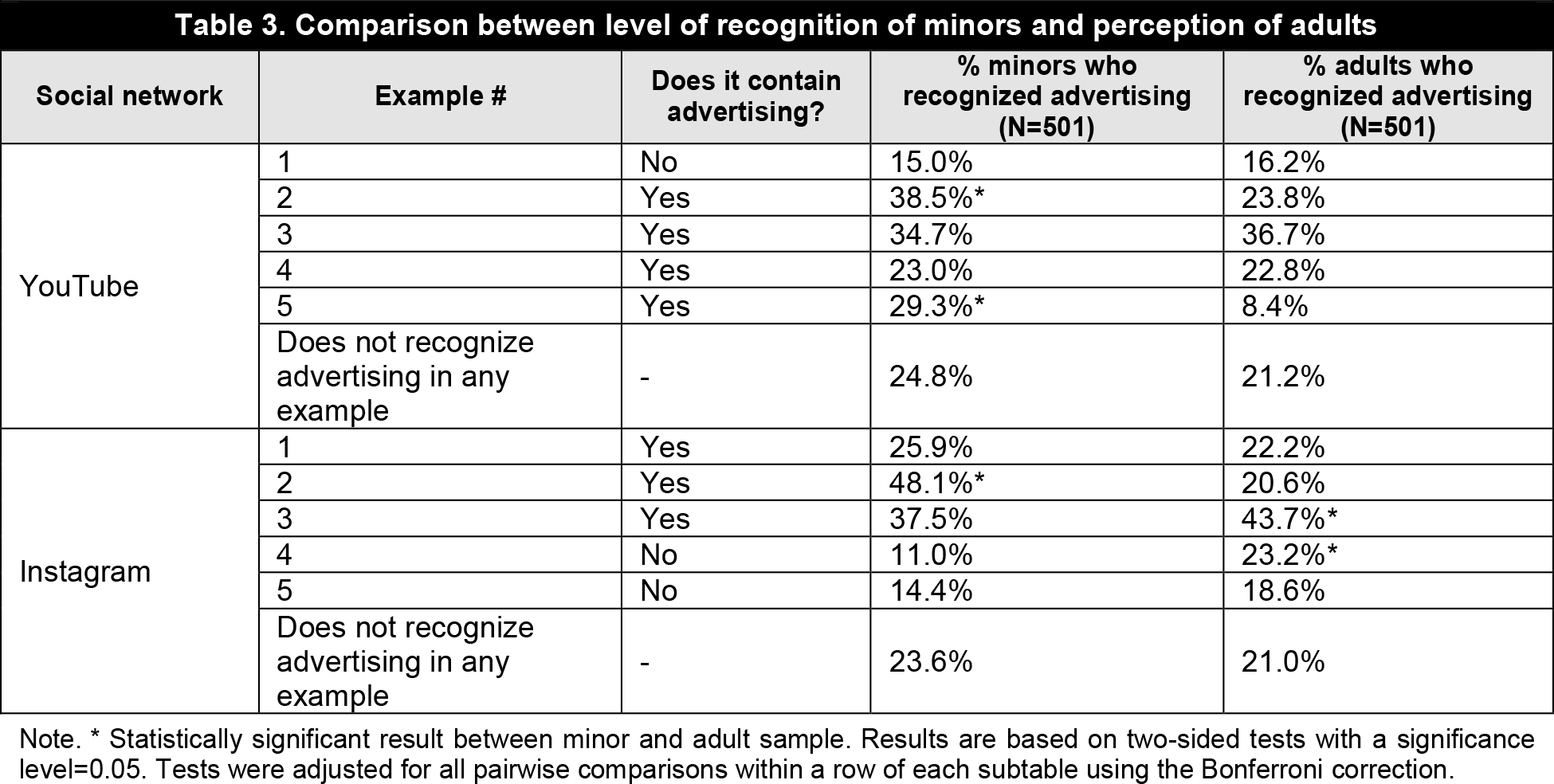

More than half of the respondents were unable to recognize advertising when it was present. Also, as shown in Table 3, almost 25% of the sample directly responded that no advertising had been identified in the selected examples, in neither YouTube nor Instagram. Advertising recognition was higher for Instagram than YouTube. Overall, YouTube concentrated the lowest detection percentages, specifically in example 4.

As already indicated in the methodology, examples that did not contain advertising were inserted among the selected cases. However, between 11% and 15% of children identified persuasive intent in these examples (1 on YouTube; images 4 and 5 on Instagram).

Recognition of advertising per platform and format, proved highest for YouTube, for which the presence of advertising in example 2 was identified by the highest percentage (38.5%), which corresponded to an ad displayed to the right of the featured video, topping the list of YouTube’s suggestions. A 34.7% pointed to example 3, a video in which the Haacks brothers, two influencers, announced on their YouTube channel having become the new image for a candy brand. Next was a standard skippable video ad (example 5) which was recognized by 29.3% of the minors surveyed, while 23% identified persuasive intent in a giveaway for electronic devices organized by YouTuber Makiman131 (example 4) as part of the content of one of his videos.

Regarding Instagram, almost 50% of the minors recognized the ad inserted in stories (example 2), while 37.5% identified the publication by singer Selena Gómez with a bottle of Coca-Cola as advertising (example 3). As indicated in the methodology section, the #ad tag was inserted in the description section in the publication. To a lesser extent (25.9%), the minors surveyed detected product placement (wine bottles) without any type of signage in the publication featuring Leo Messi (example 1).

Minors identified to a lesser extent cases in which the persuasive intention appeared intermingled with the content of the publication and with no signaling as such (example 4 on YouTube and example 1 on Instagram.)

When differentiating recognition of advertising by gender, age and socioeconomic level, age is the variable showing statistically significant differences. As can be seen in Table 4, recognition among children ages 13 to 14 years was higher in the examples containing advertising, except for example 1 on the YouTube platform, which did not contain any commercial message. The differences are more significant on YouTube than on Instagram. Similarly, the percentage of children who did not recognize advertising in any case is significantly higher among those aged 10 to 12.

Regarding gender, no significant differences were found with the exception of the Instagram advertising example taken from Leo Messi’s account, which was recognized to a greater extent by boys than by girls. A higher proportion of boys than girls did not recognize advertising in any of the cases they were shown.

With regard to socioeconomic level, the Bonferroni test barely showed significant differences. In general, a higher percentage of children belonging to the C1 level tended to recognize advertising on YouTube better than on Instagram compared to other socioeconomic levels. However, it is also the group that failed to recognize as advertising any of the examples on the two platforms studied in greatest proportion. On Instagram, the minors in group C2 obtained a higher recognition rate than the rest of the groups.

These results show that the percentage of children who correctly recognized persuasive intentionality did not exceed 7%. Total/Full/Correct recognition is understood as both having marked those examples that contained commercial information as so and indicating no advertising present when there was none. Table 5 shows that full recognition is higher on Instagram than on YouTube. Similarly, null recognition on YouTube was detected by almost 7% of the sample, while on Instagram, null recognition did not reach 0.5%. Likewise, 61% of the children correctly recognized 1 or 2 YouTube cases, and more than 70% correctly recognized 2 or 3 Instagram cases.

Perception of families on the ability of minors to recognize advertising

The percentage of children able to recognize a persuasive message in the selected cases, in general, was higher than the percentage of parents who stated that their children would perceive an advertising message. As shown in Table 3, except in two cases (example 3 on YouTube and Instagram), the percentage of adults who indicated that the minor would recognize advertising was lower than the percentage of children who actually recognized the presence of advertising. Likewise, in those cases where no persuasive intent was present, the percentage of adults who stated that their children would perceive advertising, was higher than the percentage of children who actually recognized the presence of intentionality. In the case of Instagram, this difference was statistically significant (example 3).

It is interesting to note that for the examples that contained standard advertising formats (example 5 on YouTube and example 2 on Instagram), the percentage of adults who believed that their child would recognize advertising is significantly lower than the percentage of minors who actually identified it. However, in examples No. 3 on YouTube and on Instagram, in which the insertion of advertising is subtler, parents trusted their children’s level of identification would be higher.

Ignoring whether minors had been successful in recognizing the presence (or absence) of persuasive intent, the level of correspondence between the responses of adults and minors was analyzed. As can be seen in Table 6, high minor/adult agreement (established as 4 or 5 coincidences) was reached by a little under half of the sample on YouTube and Instagram; about a third reached average agreement (3 coincidences) on both platforms, and approximately 20% reached low agreement (1 or 2 coincidences).

Discussion

The data obtained in this study opens the door to questioning the ability of minors to recognize advertising on social networks, especially when it appears mixed with other types of content.

The lowest recognition percentages were reached by hybrid formats which are not classified as advertising, such as the product placement information on YouTube and Instagram. This result is in line with the research hypotheses of previous authors (Mallinckrodt & Mizerski, 2007; An et al., 2014; Van-Reijmersdal et al., 2017; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017) which assumes that, in the face of these new types of advertising formats, children seem to devote fewer cognitive resources to recognizing subtler or covert persuasive messages.

In general, standard advertising formats had higher levels of detection than those that intermixed types of content. Thus, the lowest detection rates (less than 26%) correspond to product placement videos on YouTube (a YouTuber raffling a Super Nintendo) and on Instagram (Leo Messi with two bottles of Vega Sicilia wine in the foreground). These two examples had no indication of being promotional content, unlike other examples (such as Instagram examples 2 and 3) that did, and which achieved higher detection rates (over 38%). It would seem as though explicit and clear signaling of advertising messages would help children to differentiate the type of content they are being exposed to on social networks.

Per platform, YouTube presented the lowest percentages of advertising identification by minors. Almost 70% of them failed to perceive persuasive intent in product placement videos. On Instagram, detection rates were also low. As previously explained, on average, standard formats, such as ads in stories, were recognized at a higher rate than other more implicit commercial messages. This study also showed that the greater the exposure to a social network, the lower the percentage of recognition of the advertising to which children are exposed. This is probably due to a decrease in the cognitive effort made by minors when they browse platforms with which they are familiar, a type of behavior previously identified by other researchers.

The fact that age is the variable that marks the most significant differences in the recognition of advertising by minors must be highlighted. As previously described by other authors (Hudders et al., 2017), maturity is key in the recognition of the advertising phenomenon, hence children’s literacy process must be in pace with their age.

When results are segmented by gender, a higher proportion of boys than girls recognized the example selected from Leo Messi's Instagram profile (example 1 Instagram) as an advertising placement. Similarly, on YouTube, boys recognized the Makiman131 console raffle as advertising to a greater extent than girls did (example 4). In the same way, girls recognized as brand presence the photo of Selena Gómez, as well as in the contents of the Haacks brothers on YouTube, which appeared on a more general channel which targets children and young people. Consequently, it would seem that children would detect advertising intent to a greater extent when there is more affinity with the subject matter of the content in which the commercial message is inserted.

With respect to the perception of parents regarding the ability of their children to identify the advertising phenomenon in this study, in general, adults tended to underestimate the level of advertising recognition of minors, a finding which is in line with what has already been mentioned by previous authors (Buijzen, 2014; Oates et al., 2014; Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2003). Although the aforementioned studies focused on television advertising, it could be deduced that parental perception of children’s ability to recognize advertising is independent from the support, as a result of the distrust generated by the persuasive nature of advertising per se (Young et al., 2003; Tziortzi, 2009). Therefore, a low proportion of parents’ responses (1 in 5) reached full correspondence with those made by their respective minors in the questionnaire, which could be associated with a rather relative understanding of their minor’s ability to identify persuasive messages on social networks.

Notwithstanding the methodological limitations and the research approach used here, this study does open some non-conclusive lines of thought and research. The notion of analyzing the ability of minors to recognize the advertising they are exposed to on social networks, by asking certain questions and recording the answers provided by the respondents themselves when faced with real cases, was inspired by previous studies but had never been practically applied as it was in this study. Therefore, there is a need to continue improving the scale aimed at measuring advertising literacy on new platforms and for new media.

The authors propose to continue deepening this line of qualitative research in future studies with the aim of learning how minors process promotional content that appears interspersed with entertainment. The relevance of this notion derives from the fact that recognition of advertising is undoubtedly the first step for reaching advertising literacy (An et al., 2014). Ultimately, this type of study tributes to exploring the connection between child literacy in a digital environment and child education, a link that has not been fully established in academic literature.

Conclusions

Advertising strategies are continually modified to reach different audiences, including the youngest generations in this digital age. Today, social networks take up a large part of our Internet consumption time, which is why they have become very attractive platforms for advertisers. Advertising formats that mix types of content have become particularly popular on them.

Minors seem to lack the ability to recognize the persuasive purpose of the contents where commercial and entertainment goals are mixed, in contrast to their better ability to recognize standard formats, such as ads in stories. Age is decisive for the recognition index: the older the child, the higher the success rate, which indicates that advertising literacy must adapt to the maturation process of minors.

Parents, for their part, tend to underestimate the ability of their children to recognize advertising messages on social networks, most likely the result of their own mistrust of this type of content. Literacy efforts should also reach this particularly critical population.

Finally, it should be noted that an explicit and clear signaling of advertising messages could help minors to differentiate the types of content they are exposed to on social networks. (1)